Flower Tower

In my post “Women Weave the I Ching,” I mentioned that replicas of looms capable of mechanically repeating complex designs were found in the 3rd century BCE tomb of weaving master Wan Dinu 萬氐奴 . That was a startling discovery, as she died some five hundred years before the Han Dynasty poet Wang Yi (王逸, second century CE?) gave the earliest reference to such industrial looms in “Ode to Ladies of the Loom (jifufu jī fù fù 機婦賦).”

Imagine how those Weaving Maids All day through seven of heaven’s hours Guide and arrange the silk cloth That is draped into the robes we wear. . . . The slender threads all flow along Like a star chart winding round; Push and pull, their design unfolds Now coming, now going while They seem neither to tire nor toil. 悟彼織女, 終日七襄, 爰制布帛,始垂衣裳. . . . 纖繳俱垂, 宛若星圖, 屈伸推移。 一往一來, 匪勞匪疲. wù bǐ zhī nǚ, zhōng rì qī xiāng, yuán zhì bù bó, shǐ chuí yī shang. . . . xiān jiǎo jù chuí, wǎn ruò xīng tú, qū shēn tuī yí. yī wǎng yī lái, fěi láo fěi pí.

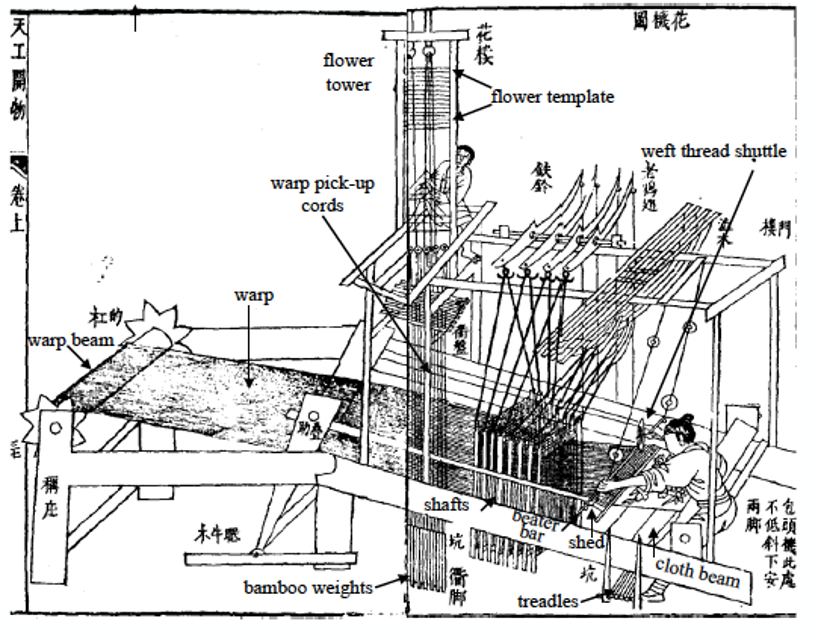

The women were working at a prototype of the loom pictured here in a seventeenth century book on the industrial arts.

Wang compares the weavers to the Weaving Maid (zhinü 織女), who makes silk for the denizens of the heavenly court near the bright star Vega. And the “slender threads” in his “star chart” metaphor are the array of cords that drop from its “flower tower (hualou 花樓)” to individual warp threads below. One weaver perched on the flower tower manipulates the warp before it gets to the shafts that the primary weaver plies with her treadles while creating a “ground weave.” If a cloth pattern calls for a peony shape, say, the flower tower weaver “pulls the flowers (tihua 提花 or tiaohua 挑花)” and draws up the warp threads that will plant the peony into the ground weave with each pass of her partner’s shuttle. That’s why this kind of loom is called a “drawloom.”

The peony image is stored in a pattern control system of strings called a “flower template (huaben 花本).” Wang calls this a “star chart,” a map of the heavens. In The Weaving Maiden’s Mystery, Lena works an apparatus that’s a riff on control systems still in use among the tribals of Southeast Asia. It’s a series of bundled string templates that come into play one by one to develop a fabric’s surface design. Lena is a super-weaver and has “fancy fingers” that execute what she sees in the Patterns of a template’s knotted strings.

Lena’s job disappeared in the early 1800s when Joseph Marie Jacquard perfected the process that had been evolving in the French textile industry and bears his name. Jacquard’s system replaced the flower template and the flower puller both with a series of pasteboard cards punched with holes that controlled mechanisms for lifting warp threads according to its patterns. Weaving thus became the first industry based on programming, and its method of managing machinery by cards was incorporated into the development of early computers. Weavers became machine operators—they set up looms and tended them as necessary, but they didn’t weave any more.

By that time, cloth factories had become the noxious sweatshops described in Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South. The mill hands, many of them children, risked life and limb for meager wages and worked long hours in the roar of machinery that deafened them to any kind of music. The loss of hands-on weaving skills was not lamented in the rush of progress. Want Yi’s poem still takes a romantic view of the job, and I suppose I could be accused of the same. His weavers worked “seven of heaven’s hours” per day—fourteen by our count, yet they “seem to neither tire nor toil.” In the ideal Confucian society, men plowed and women wove—at least among the common folk. Was Wang patronizing their “women’s work” and wishfully thinking they were happy at it?

Perhaps; but nowadays, when women are no longer forced by economics to make cloth, a good number take to weaving for pleasure. They describe the dance-like coordination of their feet and hands as a form of meditation. Maybe the ancient silk weavers also experienced a psychological lift in the flow of their repetitive motions. And the teamwork of two weavers coordinating their tasks to the kinds of songs that can still be heard among primitive weavers would have its compensations.

I have watched women who stitch the exquisite traditional style of Chinese embroidery with different images front and back, and I imagine that, like them, the old time weavers took regular breaks to do relaxing exercises based on the principles of acupuncture and massage. Fahng and her sister weavers take a nap after lunch like most of the folks I knew in Taiwan did. They practice taiji 太極 and sword gongfu 功夫 regularly. They do other things—shopping, cooking, dancing—that relieve the monotony of the work. And they sing as they work, different tunes for different weaves that blend together in a grand chorus like the songs of the hundreds of Filipinas who gather in Hong Kong’s “Little Manila” on Sundays.

They were, of course, lucky to live in Morning Song, where the government’s laissez faire attitude allowed them to run their own business. Their master, Shrpo, knows from bitter experience that their position is precarious, and she nurtures Fahng as a leader who can balance the demands of the workshop and the shifting political reality. So as for being happy, Fahng says, “Weaving is work, and it’s hard to love work. But I do it because I must. I’m satisfied. . . . If I can protect our life together, I am happy. And I am happiest when our songs of the cloth fill the workshop with harmony. Toe the treadle; throw the shuttle; beat it home; change the warp taban; tousuo; daping; Yijing 踏板; 投梭; 打平; 易經.”